RACES, RAÍCES AND RACISM: Anti-Mexican Sentiment and Ultrarunning

Because I suffered through puberty among racists, I can recite a lot of anti-Mexican jokes. Many involve athletic skill.

“Why doesn’t Mexico have an Olympic team?” a twelve-year-old white boy hissed at me during recess.

I braced myself.

“Because any Mexican that can run, jump, or swim is in the US!”

These days, I hear such rhetoric from the Oval Office. President Trump rode a wave of anti-Mexican aggression into the White House, projecting his own criminality onto us, and as he continues to harass Mexico and Mexicans from his twitter pulpit, his administration doubles down on its policy of torturing Latinx migrants in concentration camps.

Trump’s anti-Mexican rhetoric has emboldened California’s racists, and on June 8th, I encountered a small army of them at San Diego 100, an ultramarathon held near the Mexico-United States border. A one-hundred-mile race that cuts through Mount Laguna Recreational Area, the Pacific Crest, Noble Canyon, and Lake Cuyumaca Trails, the SD 100 operates under permit on the Cleveland National Forest. While the race’s website claims that the SD 100 is “an equal opportunity provider, employer and lender,” volunteers working for the event contradicted this mission.

I’m a writer of Mexican indigenous ancestry, and this set of circumstances makes my encounter with anti-Mexican racism at an ultramarathon exquisitely ironic. The athletic traditions of the Rarámuri, a native Mexican tribe whose name translates to “the one with light feet,” sparked the current interest in and spread of ultrarunning within the United States. For the Rarámuri, however, the practice had little to do with recreation and everything to do with survival. According to scholars George Van Otten, and John A. Dutton, the Spanish who arrived on Rarámuri land soon discovered silver. They then raided the tribe’s villages and enslaved children, forcing them to work the mines. Many Rarámuri escaped to the Sierra Madre Occidental, taking refuge in oaken mountains. Rarámuri ultrarunning developed as a direct response to white supremacy in North America.

In an absurd reversal of history, it became I who was chased out of the mountains by white people volunteering at the SD 100. Geoff Cordner, a photographer and ultrarunner, invited me to travel with him to Cleveland National Forest to spectate and cheer for friends running the race. He planned this trip as a way to introduce me to the American ultrarunning community, but the experience immediately turned ugly. As we approached an SD 100 aid station staffed by volunteers, several of them sprang to attention, vigilantly policing a trail. Instead of greeting us with a hello, they snapped, “No crewing is allowed at this station!”

Crewing happens when volunteers provide assistance to a runner and Cordner explained our purpose, replying, “We’re here as tourists, not crew.” The volunteers continued to stare at us with suspicion, keeping eyes on me as I proceeded to hike up the trail. We followed it for about twenty minutes and then left, heading to different parts of the park where we encountered white park staff. None of them treated us with hostility.

Cordner suggested we return to the aid station because a friend, Andrea Feucht, was likely to be passing through it. Once the station volunteers noticed our approach, they again clustered on the trail, announcing that we were unwelcome. Cordner repeated that we were tourists and a middle-aged blonde woman scowled at me, turned to another white woman, and began whispering. When I approached Feucht to say hello, a heavily tattooed white man stepped in front of me, leaving less than two feet of space between us. “I’m not gonna ask you to leave,” he told me, “but they will.” He pointed at volunteers standing at a table covered in chip-filled bowls. The volunteers stared at me icily.

“Where may I throw away my gum?” I asked.

The man pointed at a trash bag knotted to the table.

I sidestepped him, making my way to the bag, and as I held my wad of gum over it, a white woman snapped, “DON’T TOUCH THE FOOD! IT’S FOR RUNNERS ONLY!” She said this to nobody else who approached the table, reserving this order for the only Mexican-American present.

I felt sick to my stomach. I felt as if these volunteers didn’t see me as a person. What they saw was an invader, a cockroach. I wanted to leave. I couldn’t defend myself against these people. They far outnumbered us and so we left.

The Mexican criminal, the Mexican thief in particular, is a classic racist trope and my attempt to not litter triggered its invocation. Trump has heartily revived it too and the stereotype is so entrenched in American popular culture that the snack company Frito Lay once televised a mascot, a moustached Mexican in a sombrero who sang, “Ay, ay, ay! I am the Frito Bandito…I love Fritos corn chips: I’ll get them from you!”

We left the station but I wanted to leave the park. Cordner suggested that we head to a different aid station, that perhaps we’d be better received there. I disagreed, predicting that we’d be treated the same way. We were. At the second station we visited, a white man marched over to stand directly in front of us, blocking our access to a path. He told us to stay off the trails. I witnessed another white volunteer repeat similar orders to other tourists of color.

I felt disgusted, shunned, and disheartened. I didn’t feel surprised. White Americans have been drawing lines for me not to cross since I was a fetus. When my mother was pregnant with me, she and my father went to purchase a tract home in a de facto white neighborhood in Orcutt, California. While she and my father waited to meet with a realtor, they spoke to one another in Spanish. When they finally met with the realtor, my father gave him financial data. The realtor punched numbers into a machine and looked up.

“Sir,” he announced, “you don’t qualify.”

My father had overheard the white buyers in front of him. These other buyers earned an income either the same as or less than his, and San Diego shares a similar history of anti-Mexican racism. Scholars Carlos M. Larralde and Richard Griswold del Castillo have chronicled it, noting that in the 1920s, the city’s Ku Klux Klan chapter, Exalted Cyclops of San Diego No. 64, targeted Mexican immigrants for discrimination and violence. Mercedes Acasan Garcia, a female veteran of the Mexican Revolution, stated that in San Diego, “any Mexican worker who challenged authority or appeared suspicious of one thing or another would forfeit his life.” V. Wayne Kenaston Jr., whose father received the title “Klan Giant” for his leadership, recalled his mother sewing him a miniature Klan robe and hood. Kenaston Jr. also revealed that the Klan chiefly existed to “[chase] the wetbacks across the border.” Garcia, who worked as a maid for a white family, recalled seeing Mexicans dragged, lynched, whipped, and burned.

As the century progressed, the San Diego Klan grew stronger. By the 1980s, members boasted of beheading Mexicans and dumping their bodies in the desert. Mexican-American activists described San Diego’s law enforcement as racially “selective,” citing that Mexicans primarily complained of police harassment and Klan beatings. Today, San Diego identifies as “America’s Finest City.” Trump, who refers to racists as “very fine people,” won 36% of the 2016 vote in San Diego County.

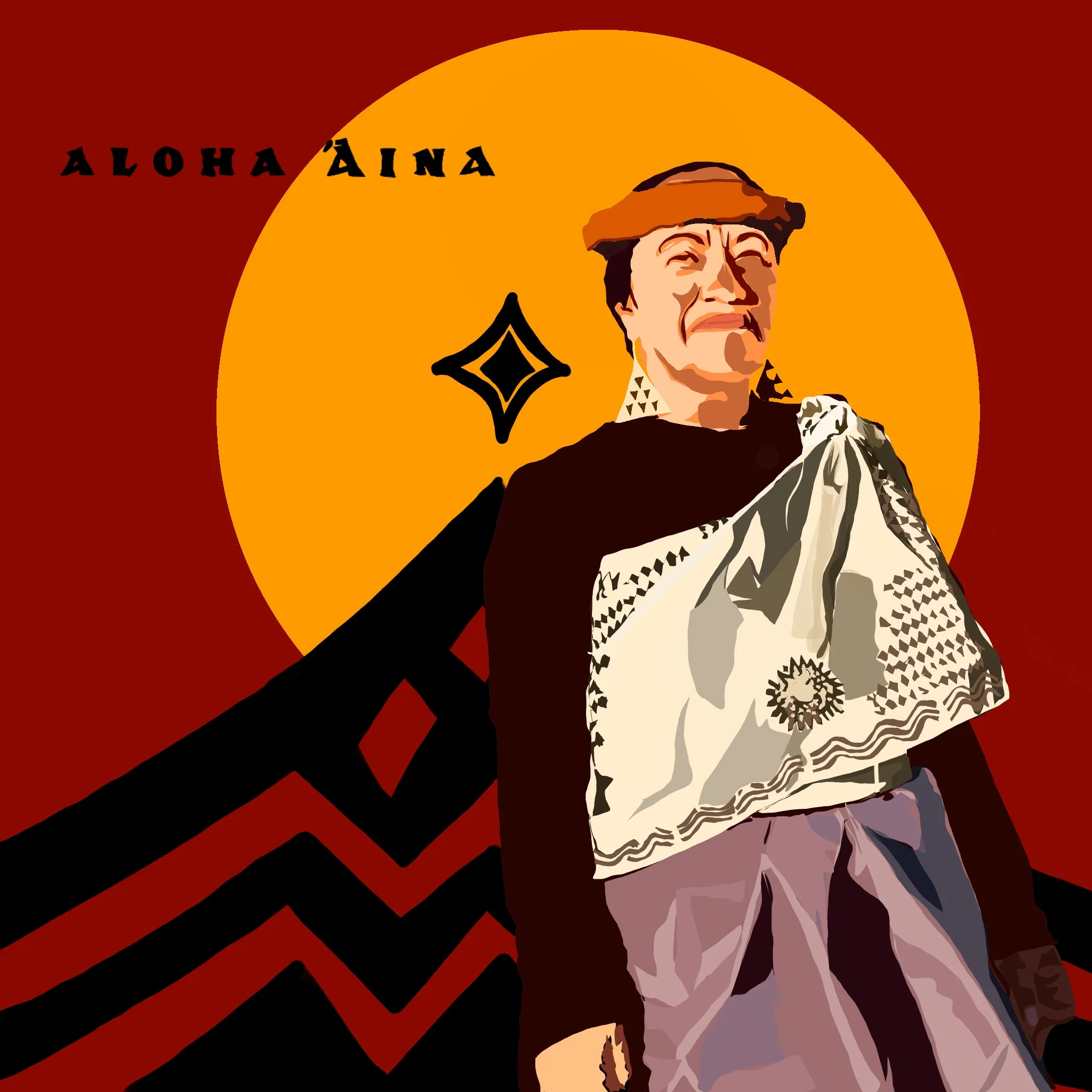

Racists rarely wear white hoods anymore. The SD 100 volunteers who mistreated me wore ball caps, matching t-shirts, shorts, and often Hoka shoes, Hoka One One having been the race’s primary sponsor. Professor Claudia Rankine has written about the “scene of race,” a phrase which echoes the scene of the crime. She locates this scene in the imagination, suggesting that we check where “the boundaries of [our] imaginative sympathy line up…with the lines drawn by power.” If one opens the May/June 2019 issue of Ultrarunning Magazine, one will find ninety-one images of runners. Of these images, one represents a person of color. Its captioned, “A runner traverses one of the many water crossings on the course.” For the runner without a name, the lines have been drawn.